Week 6

Quantitative Sociology

THE BROAD VIEW

SOCI 316

Why Quantify Society?—

March 4th

Drawing Inferences

A Random Question

Was your first impression of someone ever “off?”Drawing Inferences

First impressions often change as we gather more information—i.e., data points—allowing us to fine-tune our inferences about how person x might behave in different situations.

Just as in statistical inference, more data helps us move from crude hypotheses to well-defined expectations about how x might behave within specific situational constraints.

Drawing Inferences

Here’s a general rule-of-thumb—

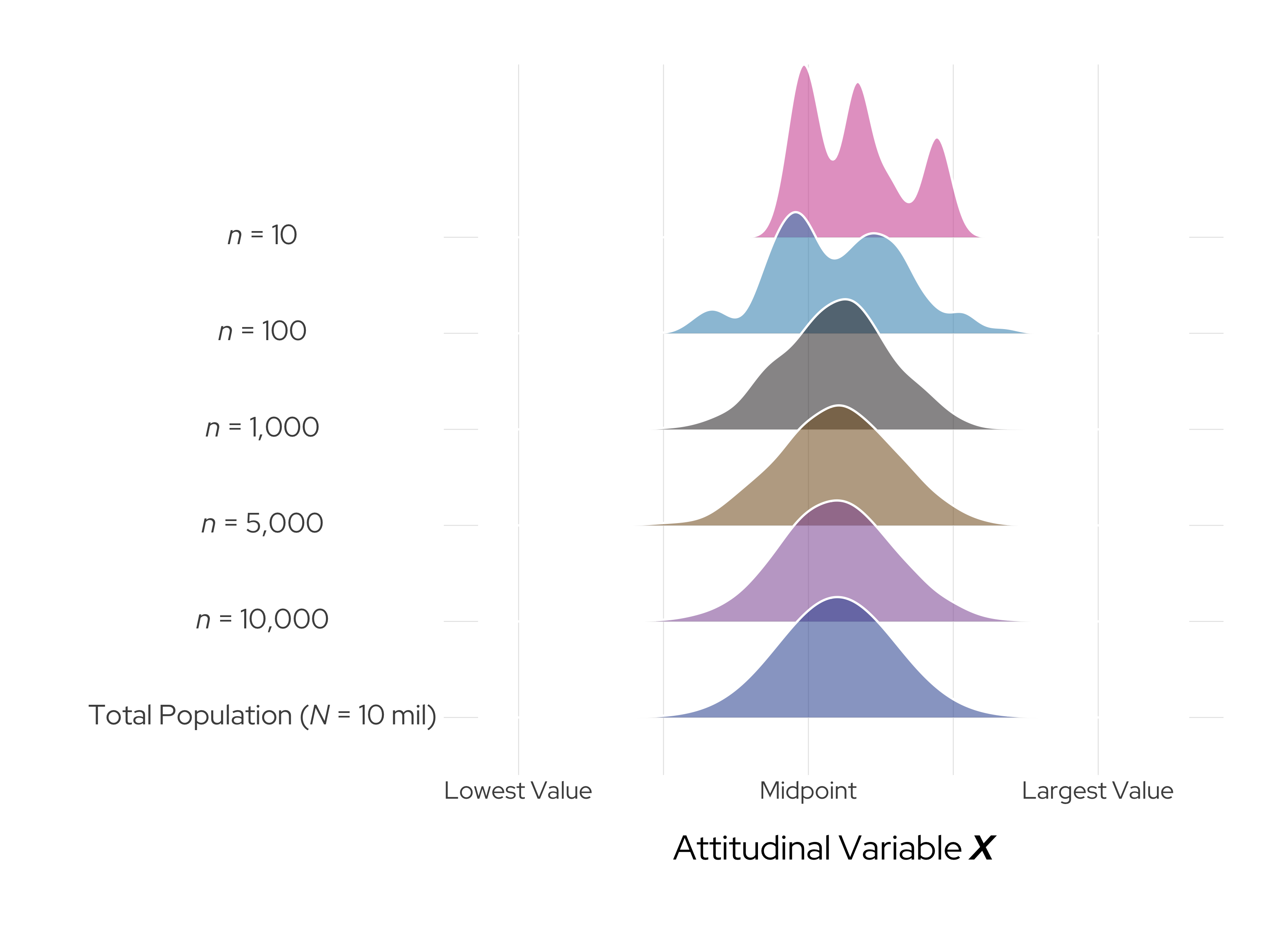

In quantitative sociological research, we often strive to generalize our findings—not just to draw inferences about person x, but to make tenable claims about U, a broader target population. To wit, we want our insights to tell us something meaningful about a large set of units—people, countries, firms, documents, etc.

Drawing Inferences

We’ll Return to This Next Week

Drawbacks?

Another Question

What are some well-known limitationsof quantitative research?

My Perspective

In my view, the benefits of quantification easily outweigh the limitations. However, your mileage may vary.Advancing Causal Claims

Does X Cause Y?

Social scientists are often interested in drawing causal inferences.

X \to Y

About what, exactly? There are a dizzying array of examples. Here are three questions that (implicity or explicitly) invite causal claims—

Do smaller class sizes improve pedagogical outcomes?

Will investments in family planning programs improve economic and health outcomes for women in low-income settings?

Did the cultural grievances of the “middle class” trigger the rise of fascist politics in interwar Europe?

Does X Cause Y?

We can, of course, deploy quantitative tools (e.g., estimators, weighting, causal diagrams, experiments) to “resolve” these questions—or at least adduce evidence grounded in statistical reasoning.

Does X Cause Y?

For simplicity, let’s assume that our (three) outcomes of substantive interest are approximately linear. Can we estimate a linear regression model to “resolve” our three research questions?

y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x + \epsilon

The Answer

It depends.Correlation \neq Causation

Some Examples

Correlation \neq Causation

Some Examples

Correlation \neq Causation

Some Examples

Correlation \neq Causation

Some Examples

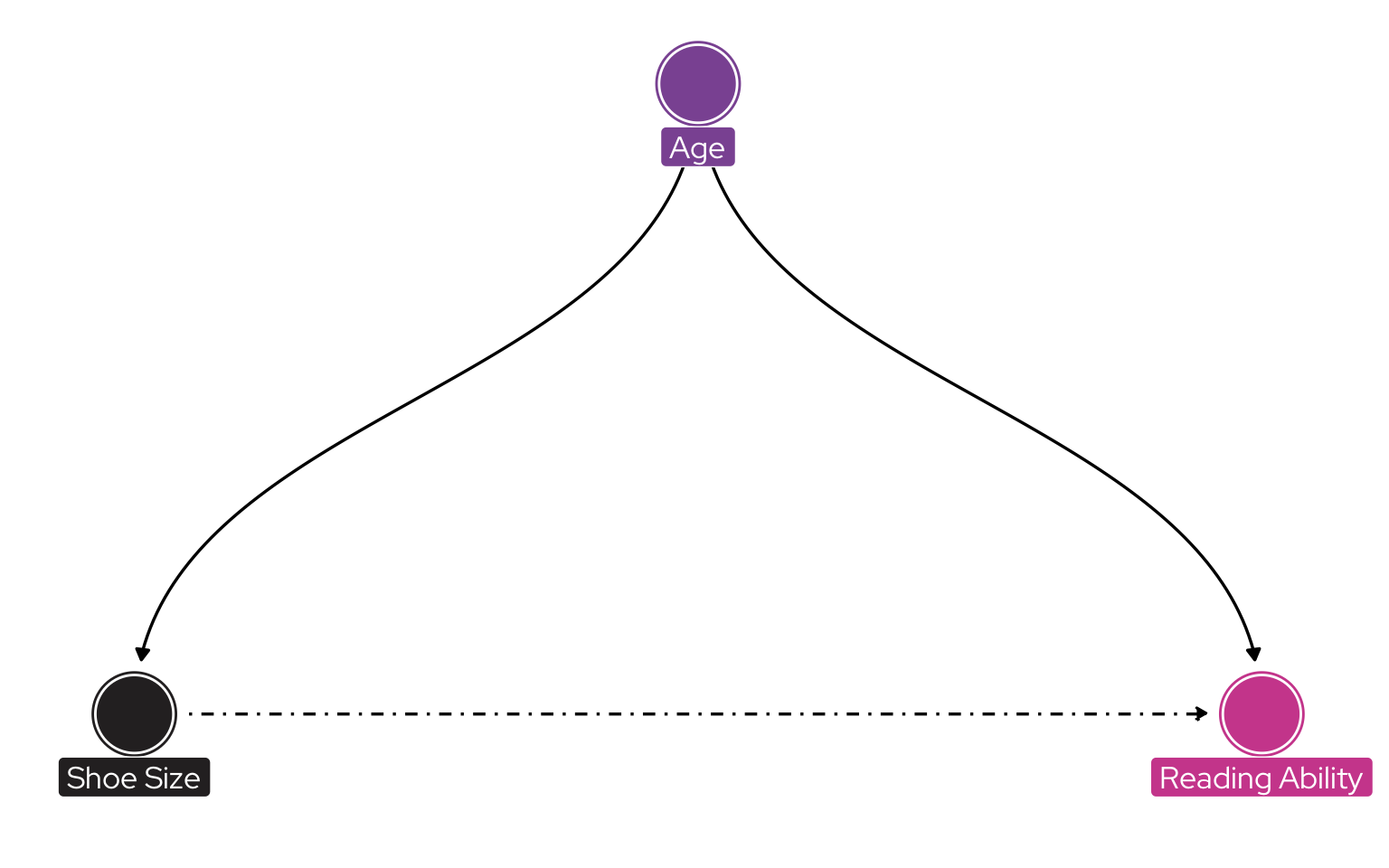

Do Not Condition on a Collider

Adaptation of Figure 4 from Elwert and Winship (2014).

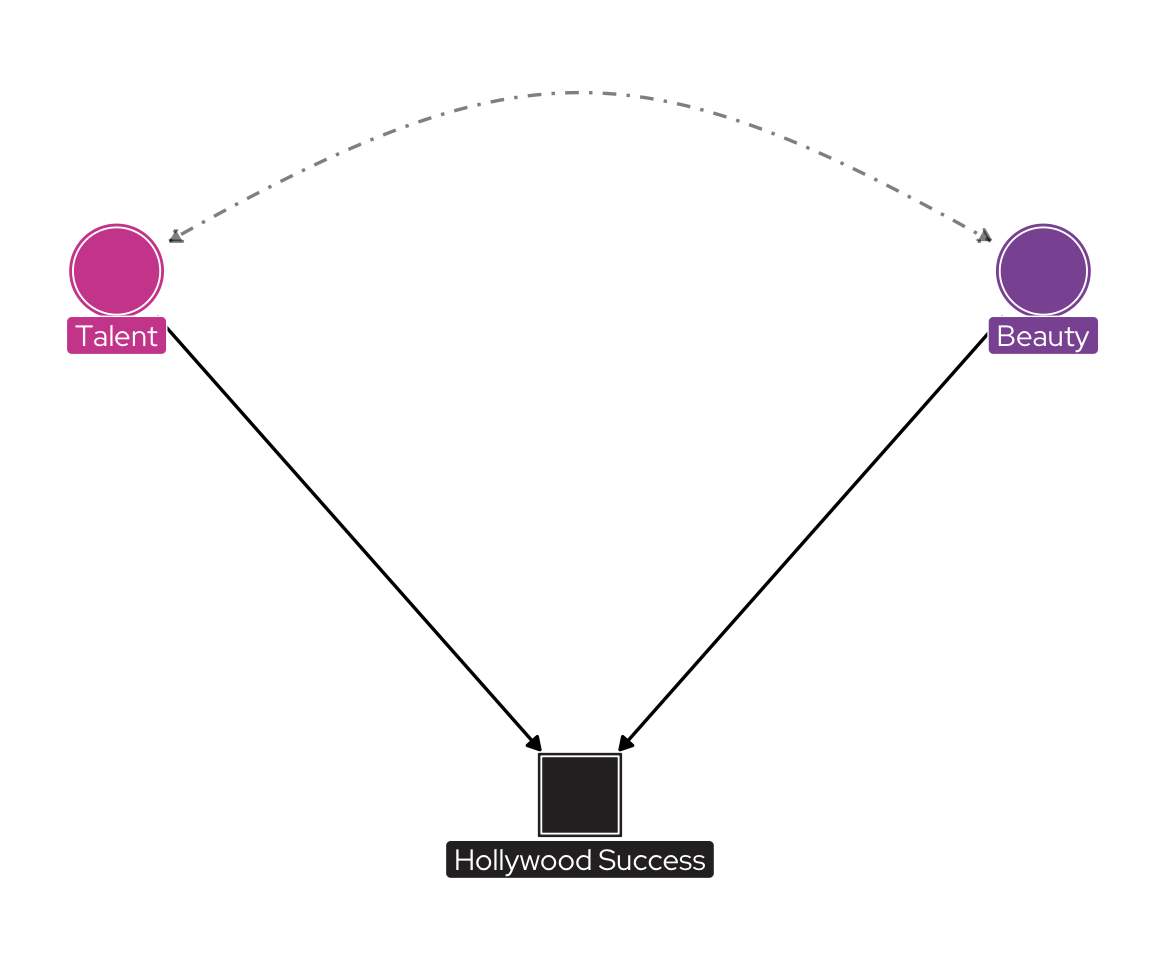

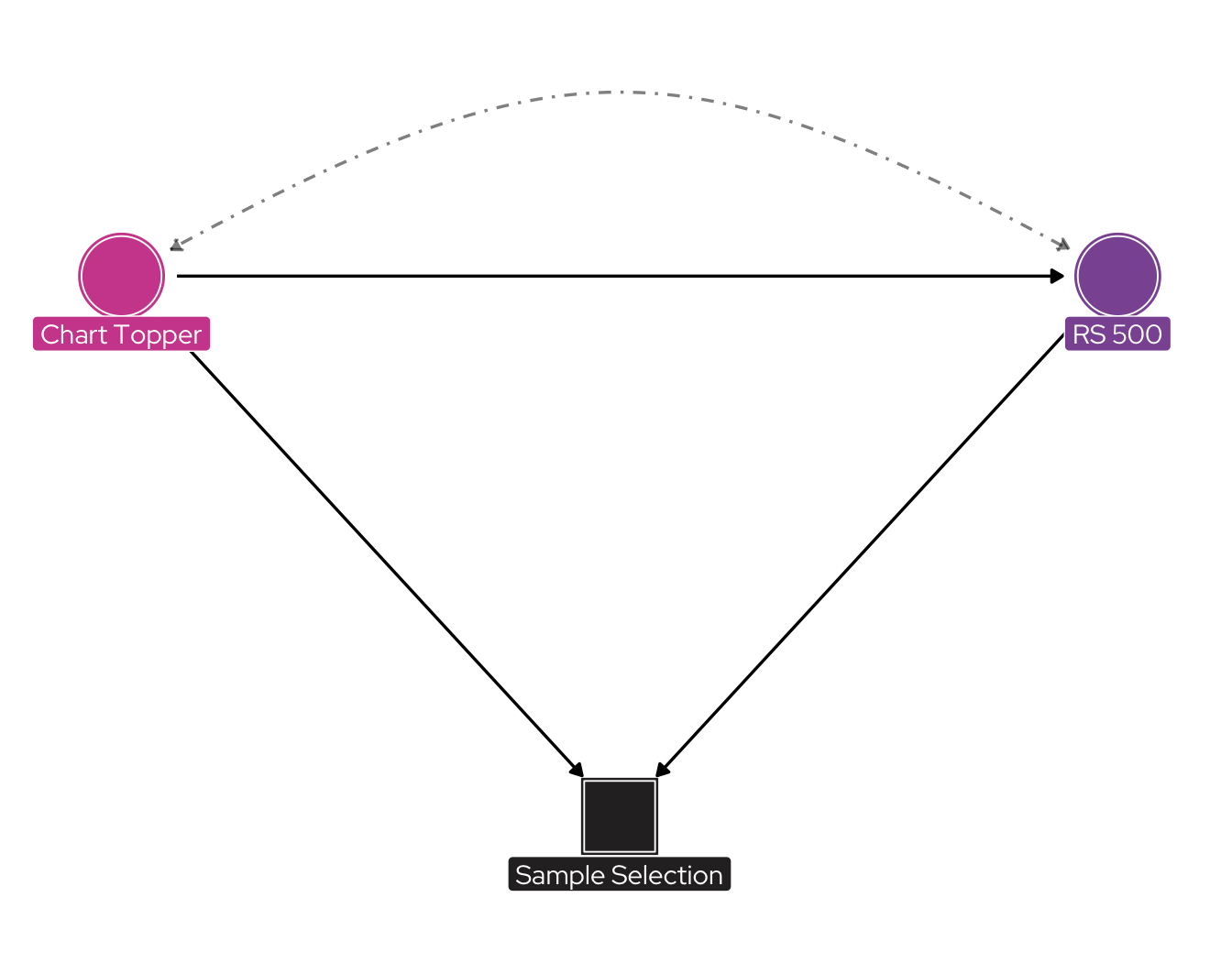

Do Not Condition on a Collider

Adaptation of Figure 7 from Elwert and Winship (2014).

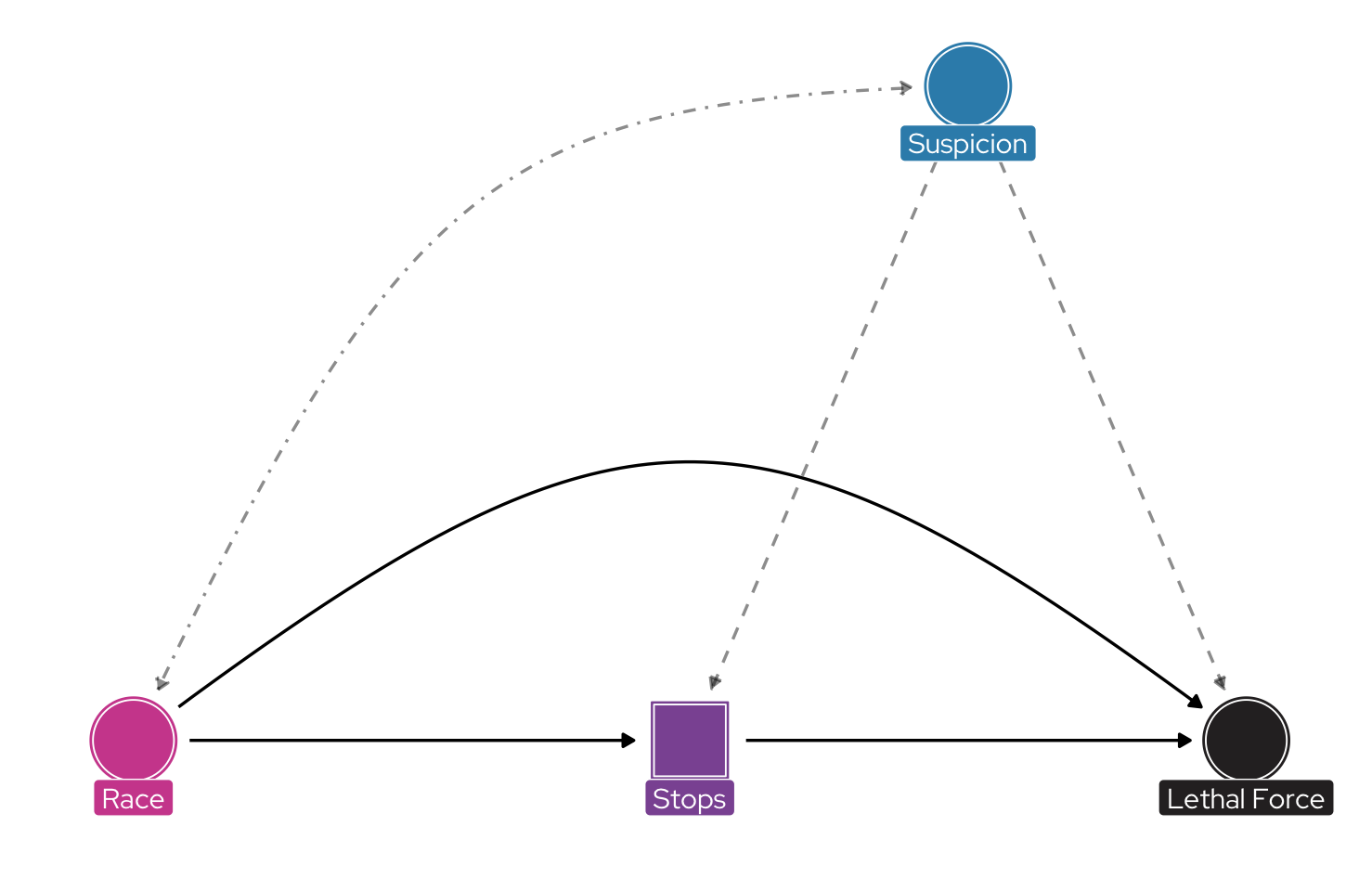

Do Not Condition on a Collider

Adaptation of Figure 1 from Knox, Lowe and Mummolo (2020).

Group Exercise I

Quantifying Your Research Projects

For the rest of today’s session, strike up a conversation with someone you don’t know particularly well.

During your discussion, please respond to the following questions—

If your project will feature a quantitative dimension, how are you planning to measure your key constructs and test your guiding assumptions about x, your phenomenon of interest?

If your project will not feature a quantitative dimension, how could you integrate quantitative data analysis into your work?

What are the causal assumptions animating your research?

Relational Approaches to Measuring Society—

March 6th

Some “Review”

A Question

Remember Abbott’s (1988) treatise on transcending a general linear reality? What exactly was he referring to?Some “Review”

How can we transcend the GLR Abbott (1988) was decrying?

Networks are, perhaps, the paradigmatic example.

A Relational View of Social Phenomena

Network-analytic techniques are inherently relational

(see Emirbayer 1997; Mohr 2013).

What About Adjudicating Causal Claims?

Are relational approaches to measurement compatible with “variable-centred” techniques and “substantialist” frameworks?

The Answer

It depends.Measuring Meaning

The Formal Analysis of Meaning

Although this resurgence of interest in cultural phenomena is often associated with the shift towards more humanistic and interpretative methodologies, an increasing number of quantitatively oriented scholars have also begun to turn their attention to the study of cultural meanings. In the process a new body of research has begun to emerge in which social practices, classificatory distinctions, and cultural artifacts of various sorts are being formally analyzed in order to reveal underlying structures of meaning.

(Mohr 1998, 345, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Formal Analysis of Meaning

Today, this body of research arguably stands

at the vanguard of the field.

The Formal Analysis of Meaning

Quantitatively-oriented analyses of “meaning” tend to

follow a basic blueprint—

… (a) basic elements within a cultural system are identified, (b) the pattern of relations between these elements is recorded, (c) a structural organization is identified by applying a pattern-preserving set of reductive principles to the system of relations, and (d) the resulting structure (which now can be used as a representation for the meaning embedded in the cultural system) is reconnected to the institutional context that is being investigated.

(Mohr 1998, 352, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Formal Analysis of Meaning

Having collected information regarding the relations of similarity (or difference) among a set of items within a cultural or institutional system, the next task is to find structure-preserving simplifications that may allow the complexity of the system to be more easily understood. Ideally, one hopes to identify some deeper, simpler, structural logic—that is, a principle or set of principles that account for the arrangement of parts within the cultural system … The relations between cultural items are the key to such an investigation. The analytical task is to discover how these relations are related to one another. Structuralist methods are geared toward the identification of transformations that allow the relations among the relations to be reduced to more easily understandable and or visible patterns.

(Mohr 1998, 356, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Two Quick Case Studies

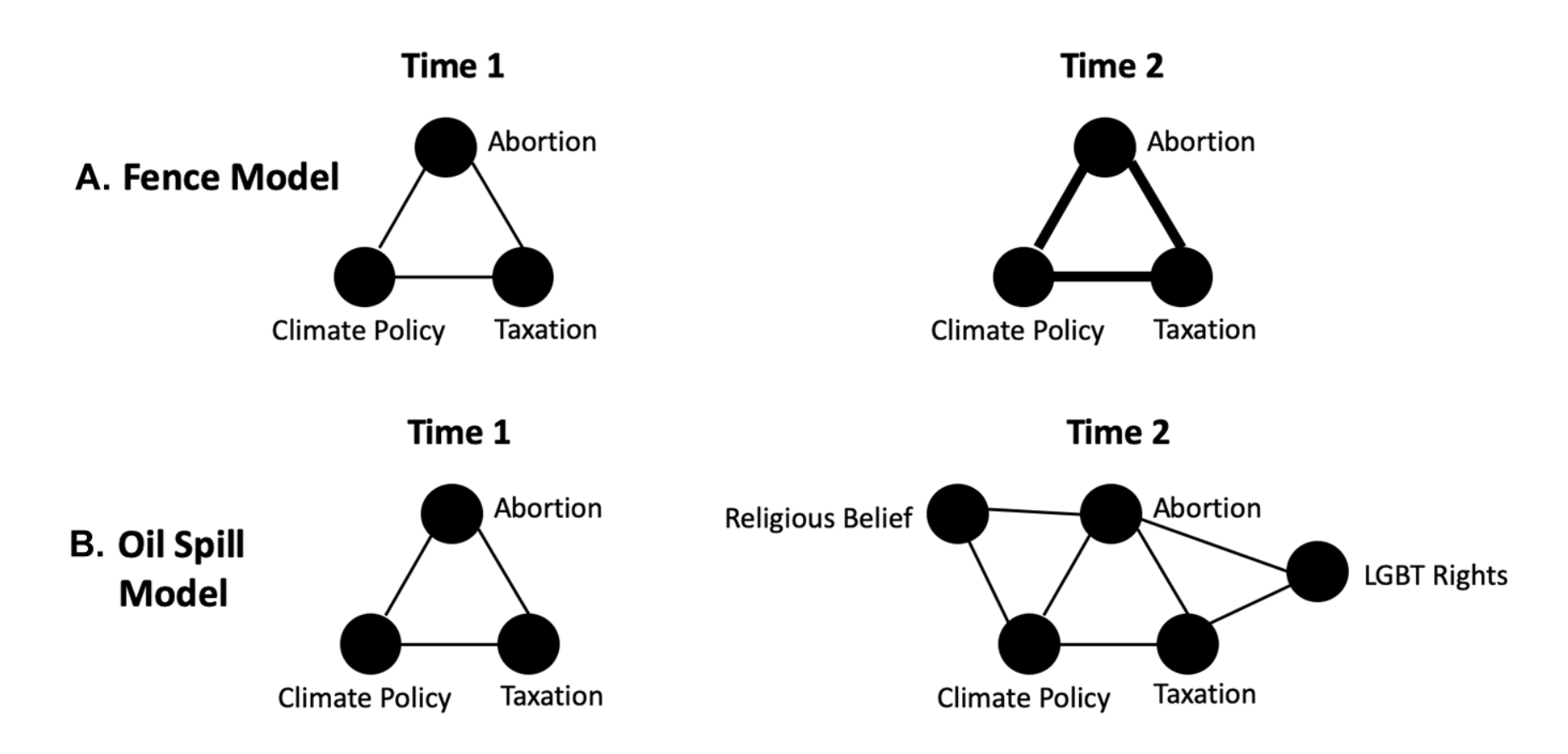

Polarization as an Oil Spill

[W]hat if polarization is less like a fence getting taller over time and more like an oil spill that spreads from its source to gradually taint more and more previously “apolitical” attitudes, opinions, and preferences? … [R]ather than heightened alignment across already-politicized opinion dimensions, the crux of contemporary polarization might lie in the increased breadth of opinions and preferences that have come to be associated with political identities and beliefs. This broadening of opinion alignment to encompass areas typically thought of as nonpolitical would not be picked up in studies that only consider polarization along existing lines of political debate.

(DellaPosta 2020, 508–9, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Polarization as an Oil Spill

Figure 1 from DellaPosta (2020).

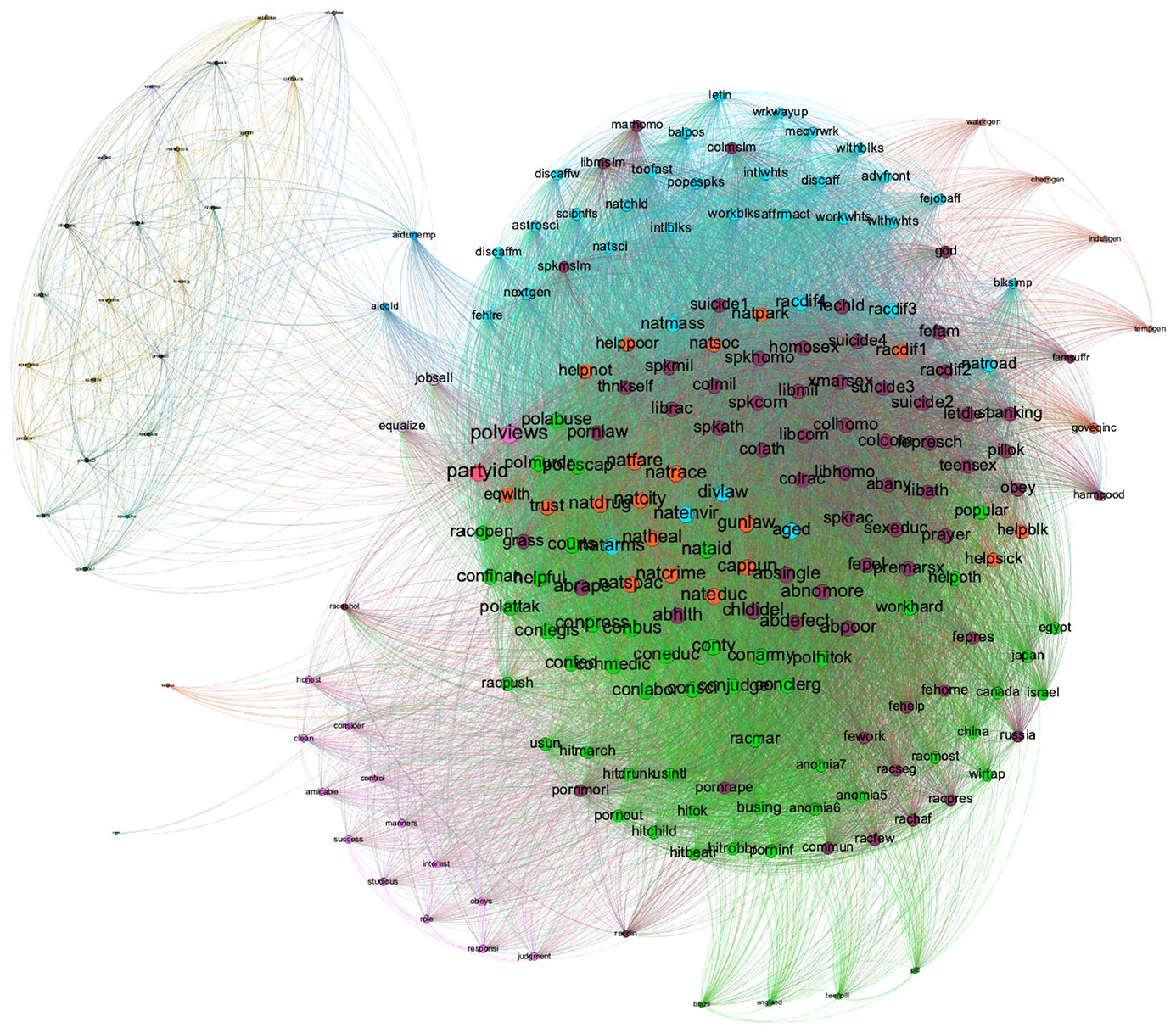

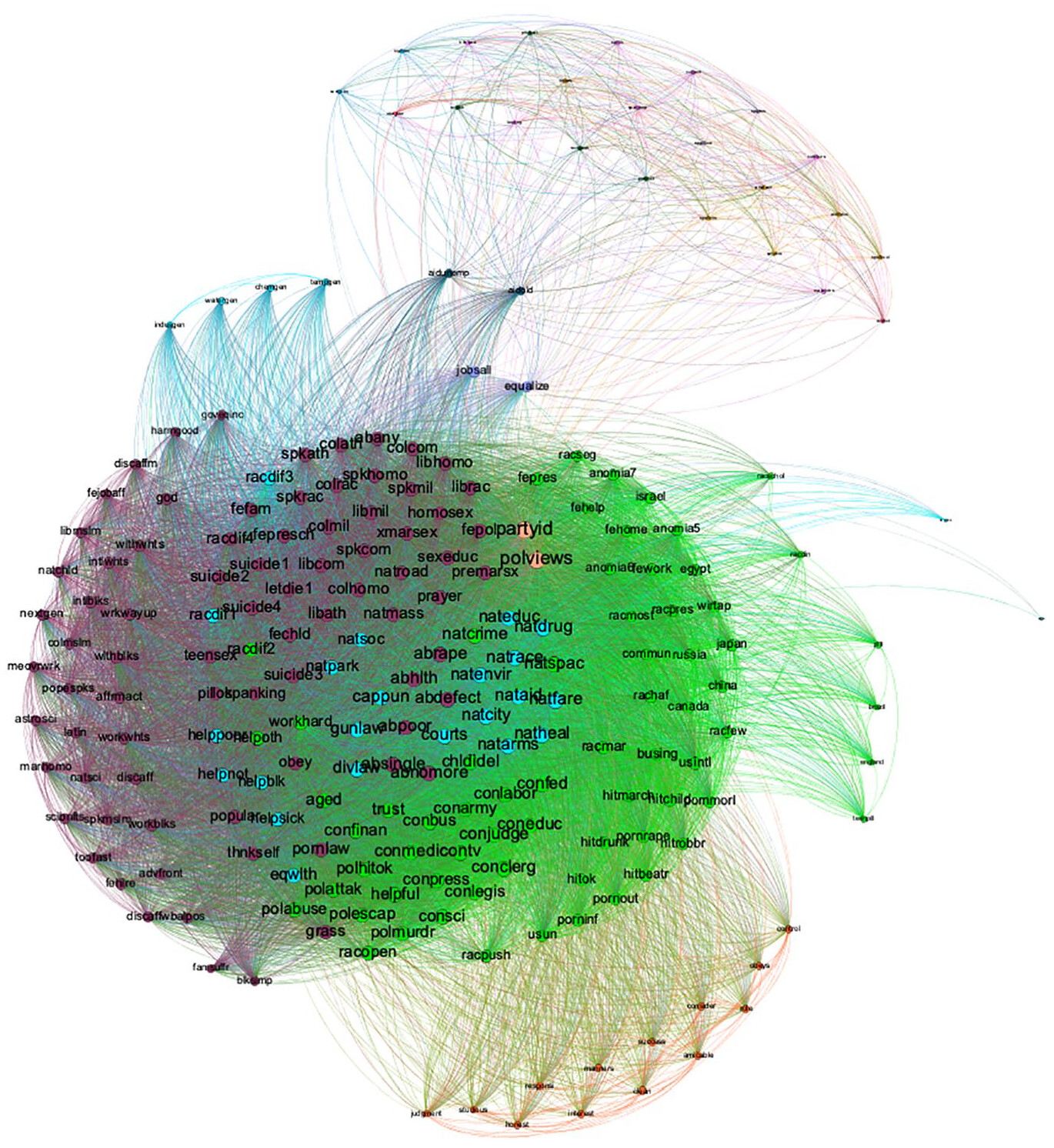

Polarization as an Oil Spill

GSS Belief Network — 1972 (DellaPosta 2020)

GSS Belief Network — 2016 (DellaPosta 2020)

Figures 4 & 5 from DellaPosta (2020).

Structured Self-Narratives

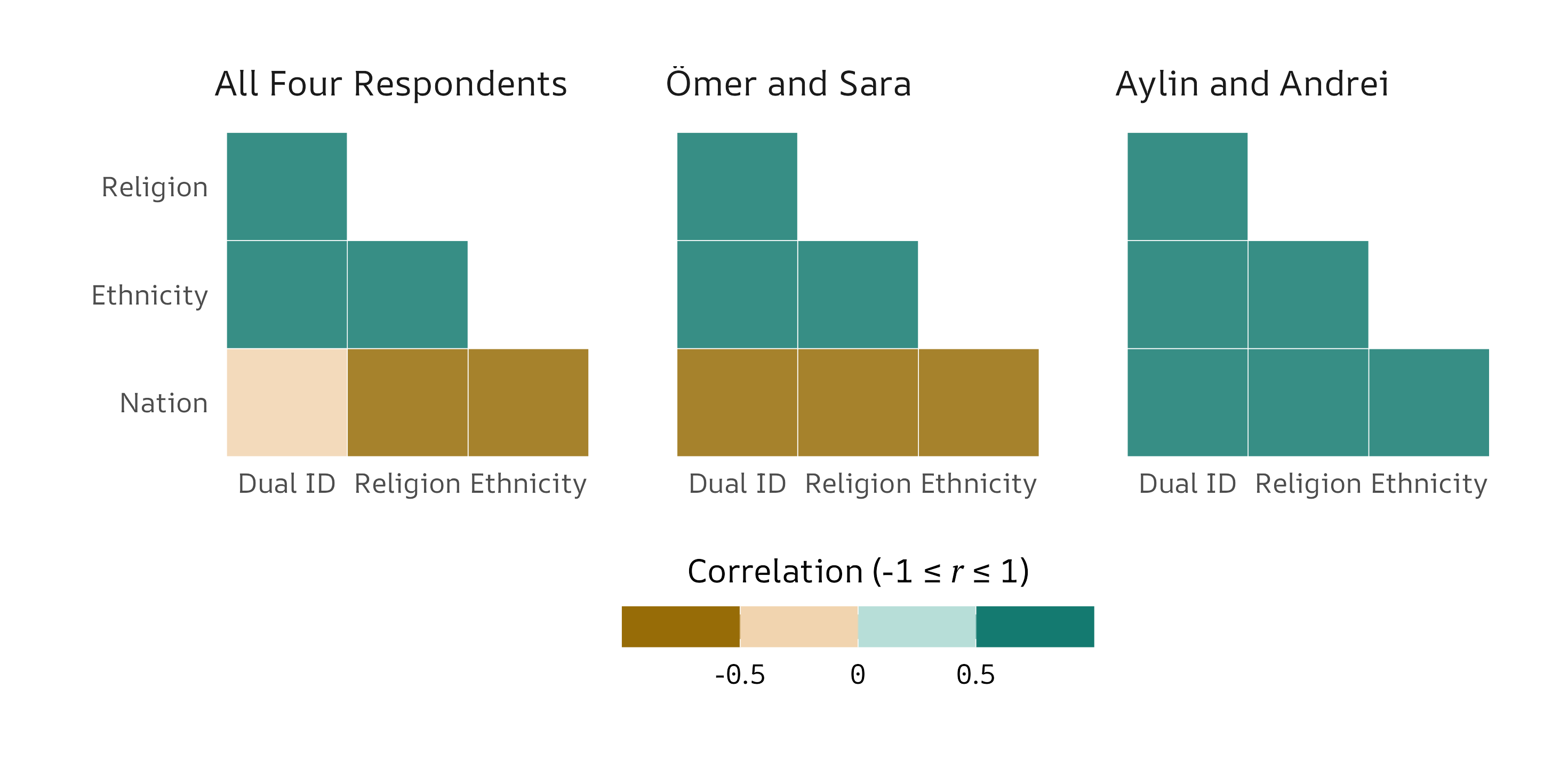

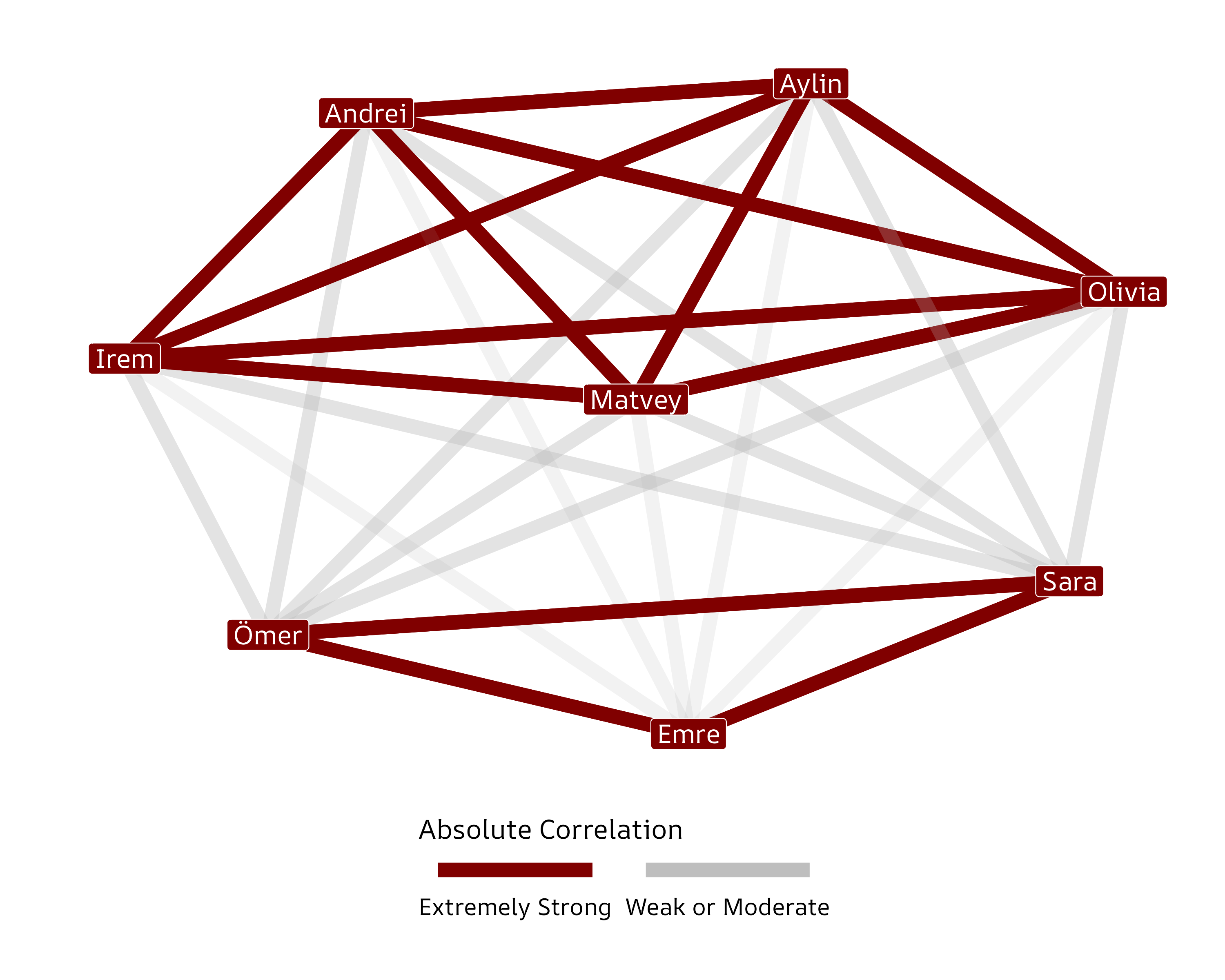

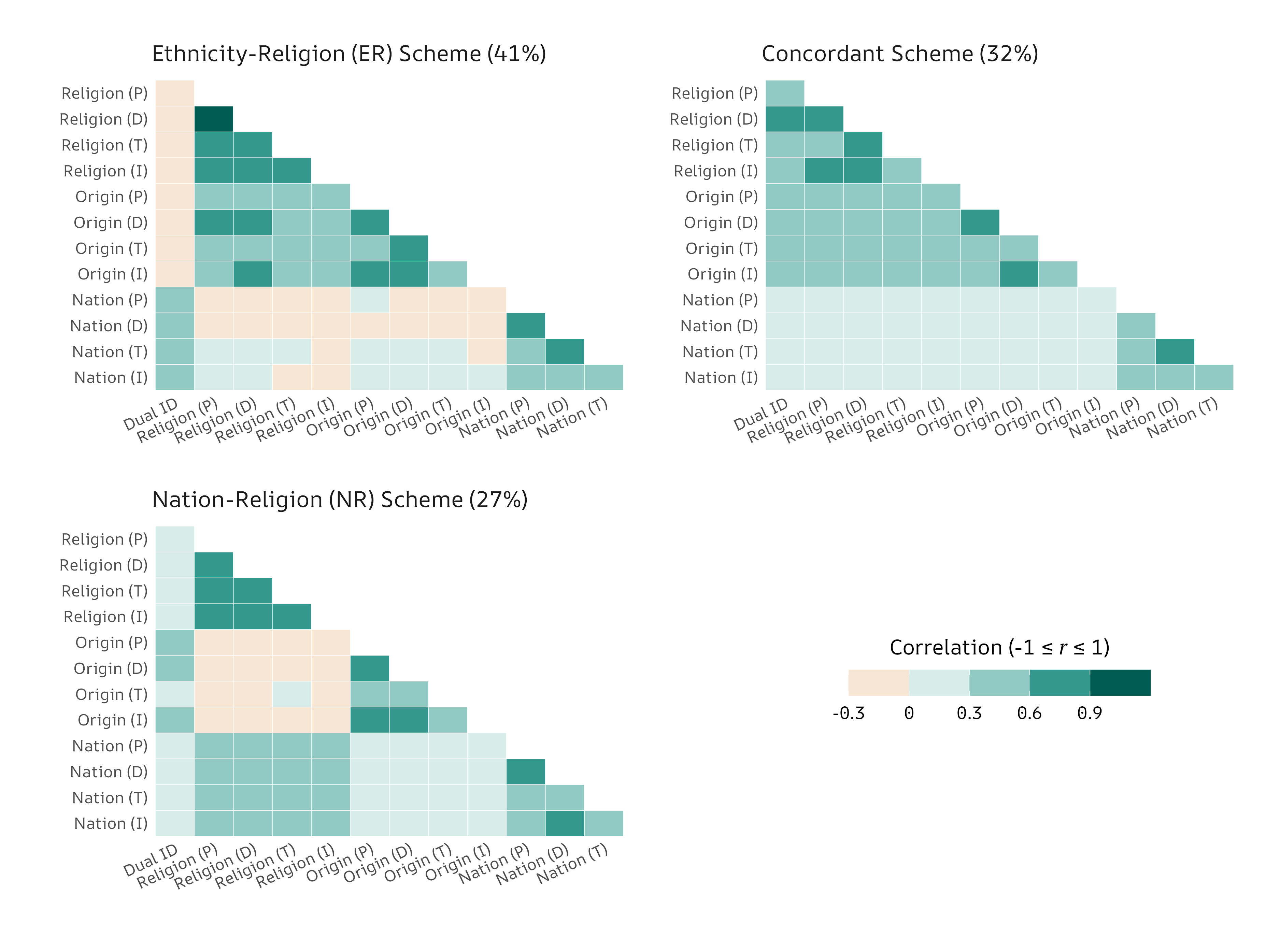

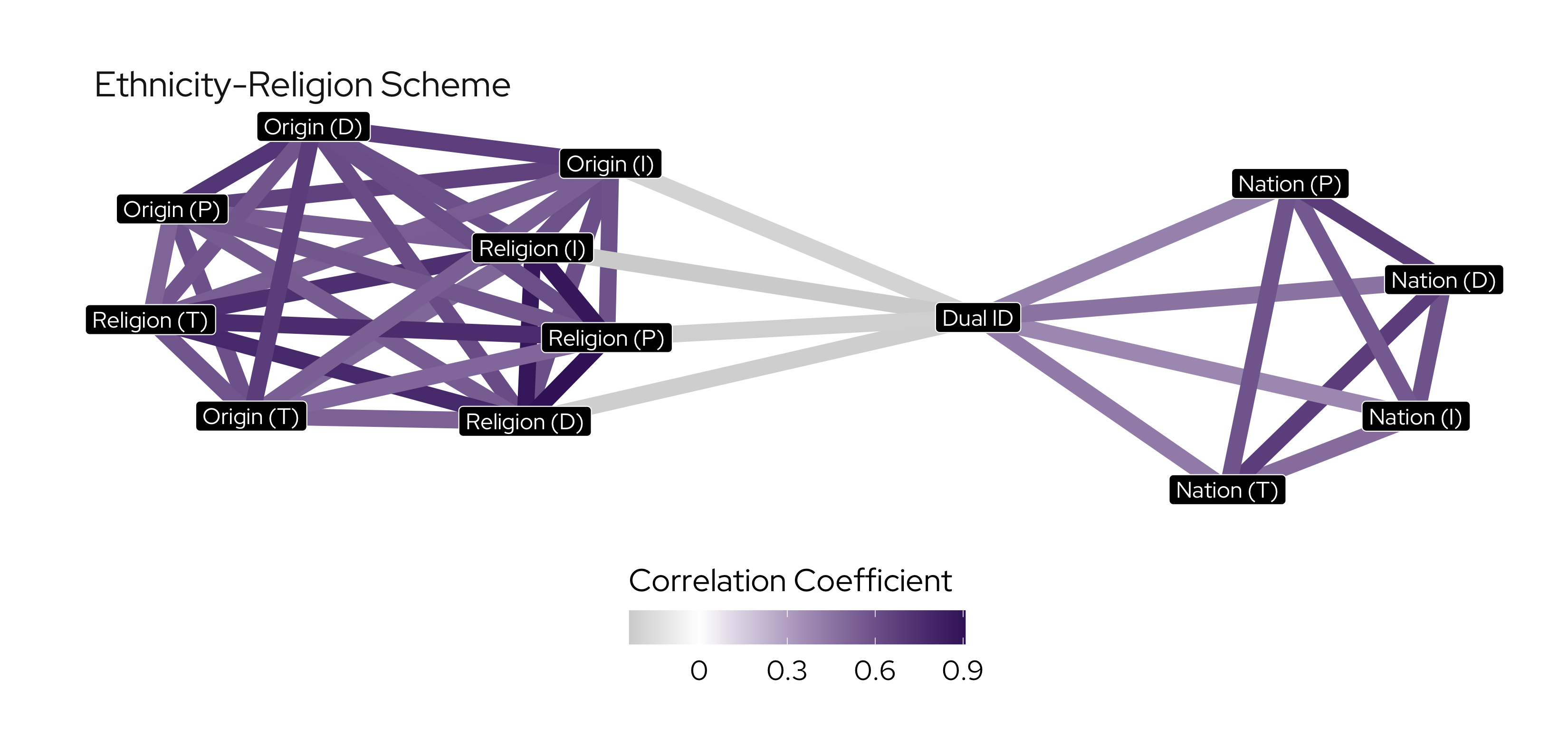

Figure 1 from Karim (2024).

Structured Self-Narratives

Figure 2 from Karim (2024).

Structured Self-Narratives

Figure 3 from Karim (2024).

Structured Self-Narratives

Adaptation of Figure 3 from Karim (2024).

Group Exercise II

Continuing the Conversation

In groups of 2-3, discuss (i) the causal assumptions underlying your research; and (ii) how you could, in principle, draw on relational techniques to measure x, your phenomenon of interest.

Enjoy the Weekend

References

Note: Scroll to access the entire bibliography

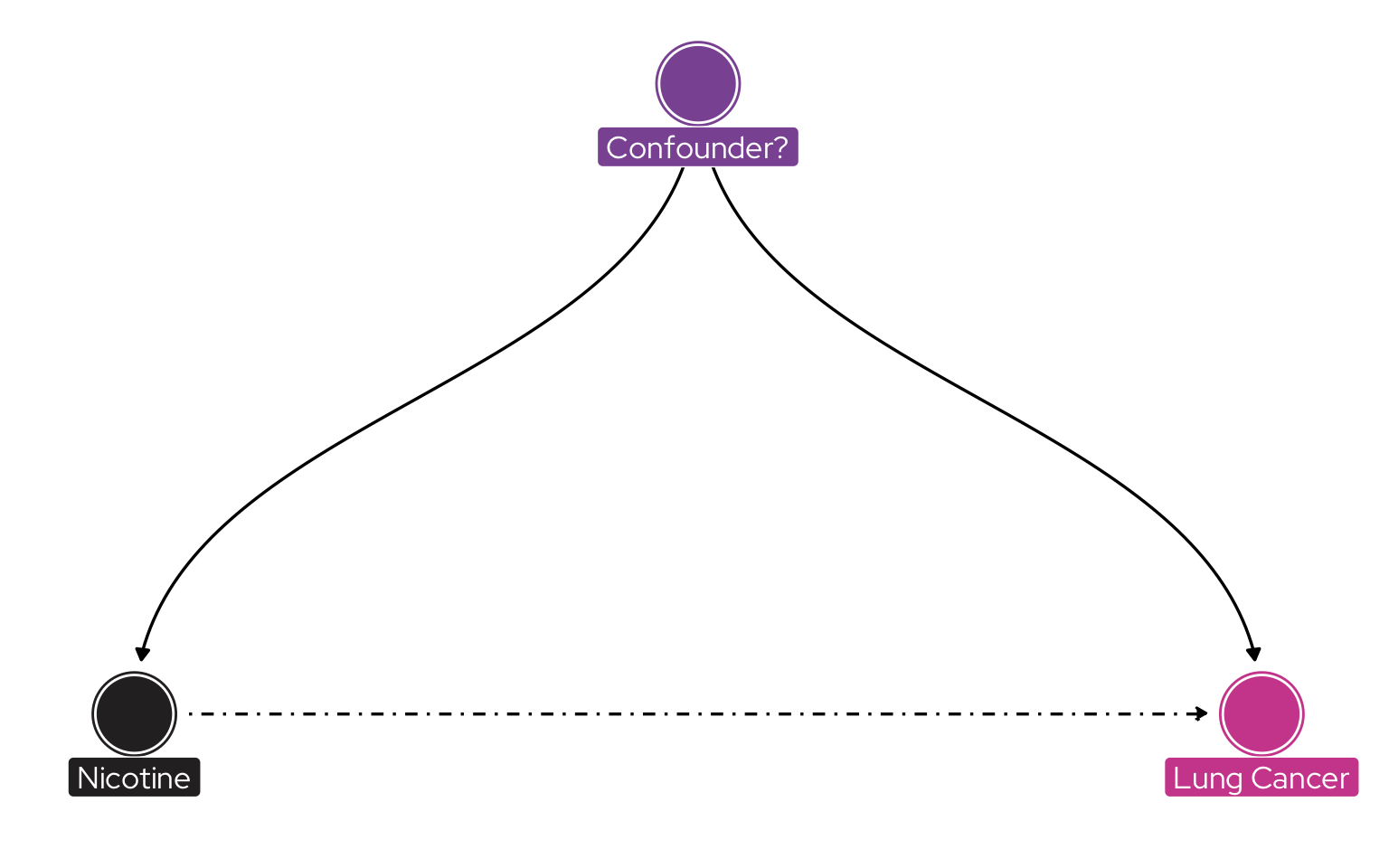

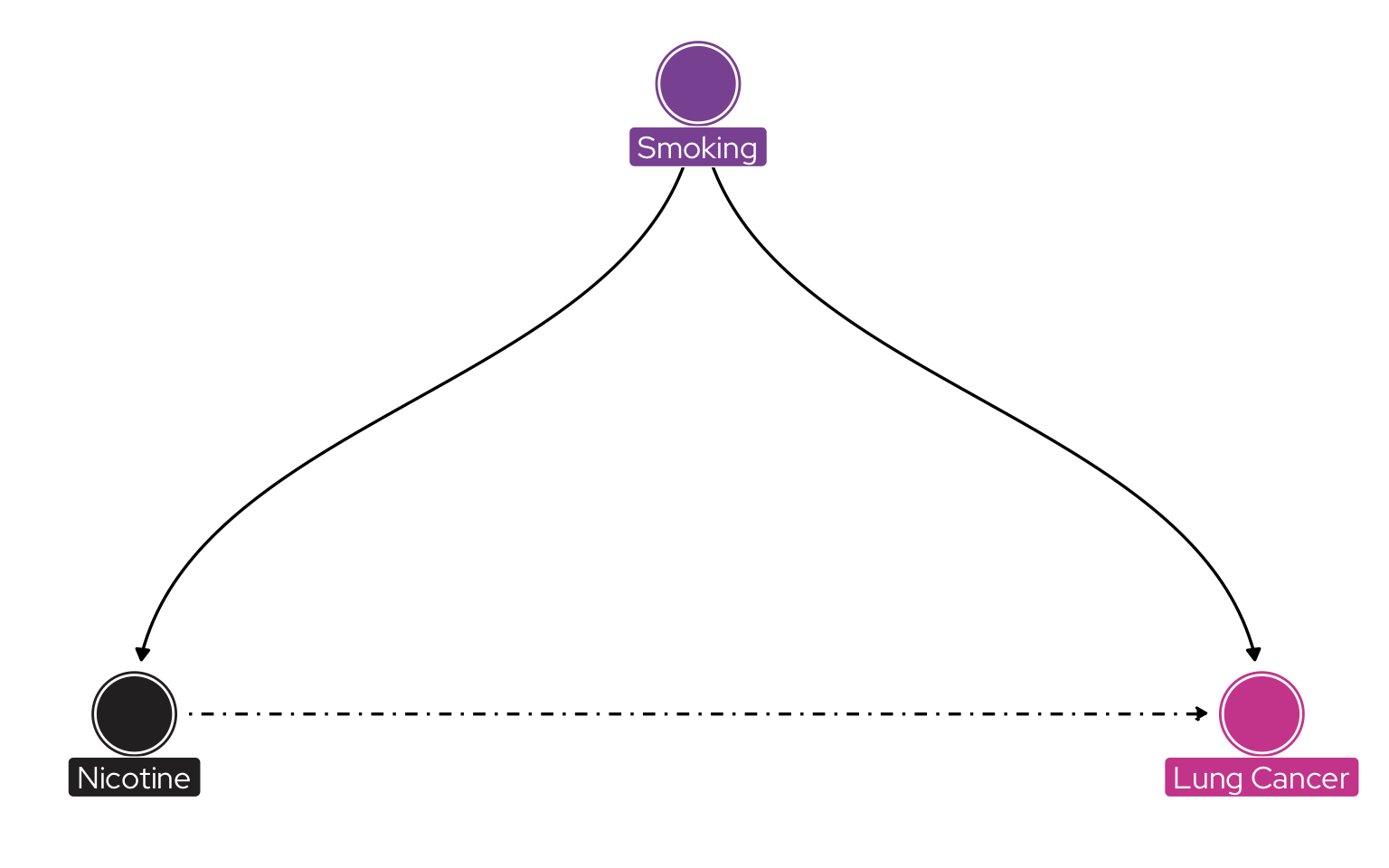

Why might nicotine consumption and lung cancer be correlated?

Smoking is the confounder in this instance.

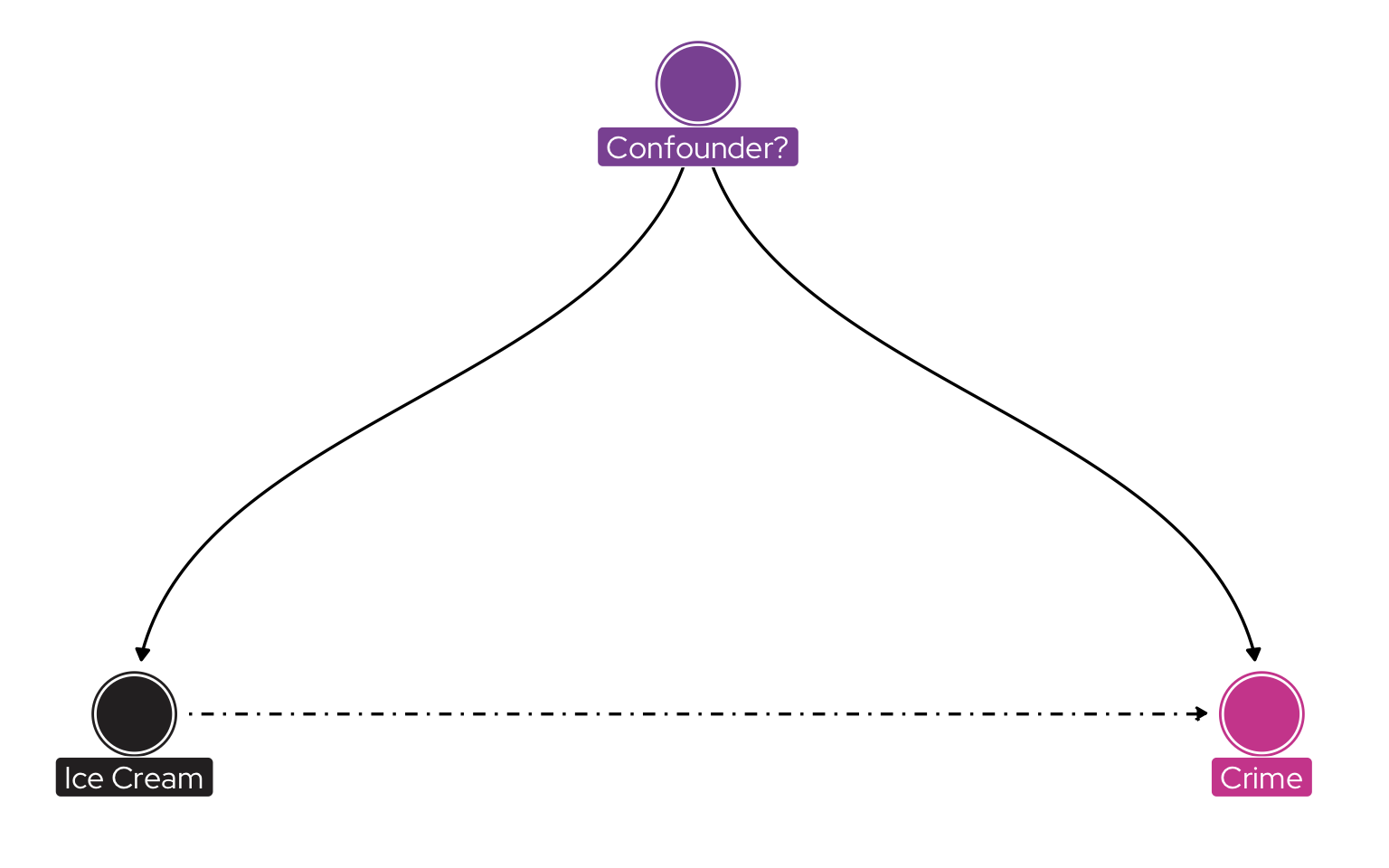

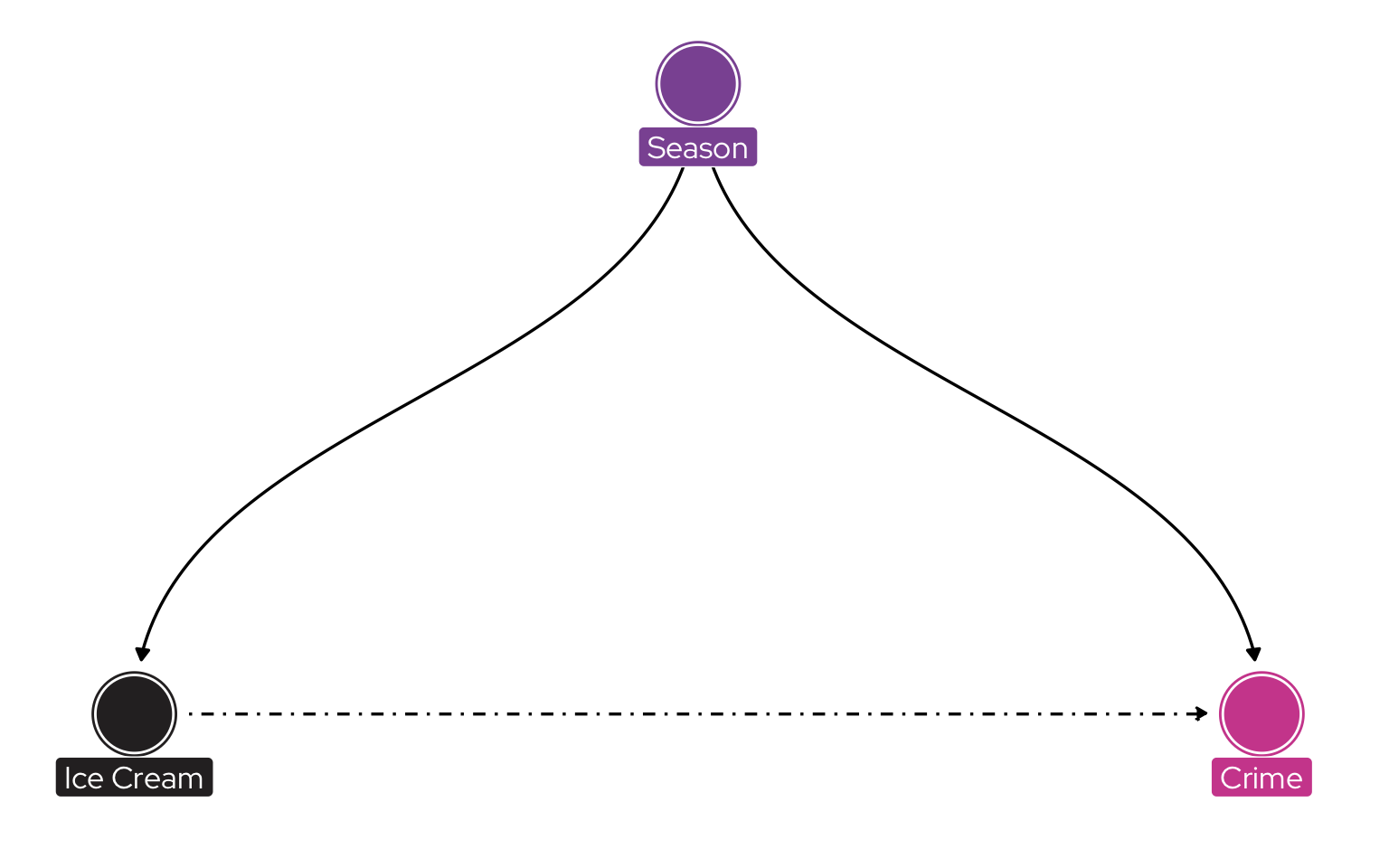

Why might ice cream sales and crime be correlated?

Season/temperature is the confounder in this instance.

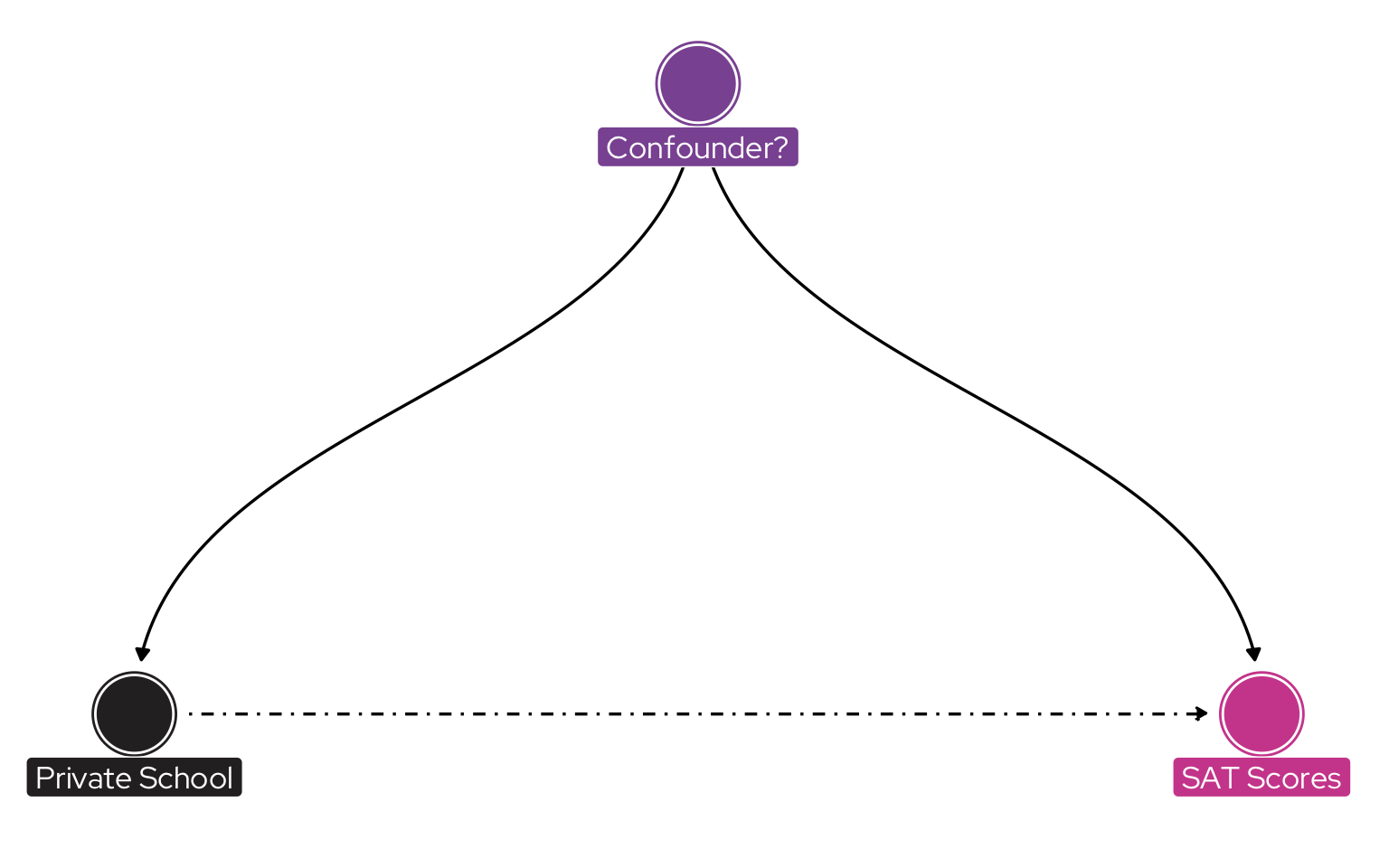

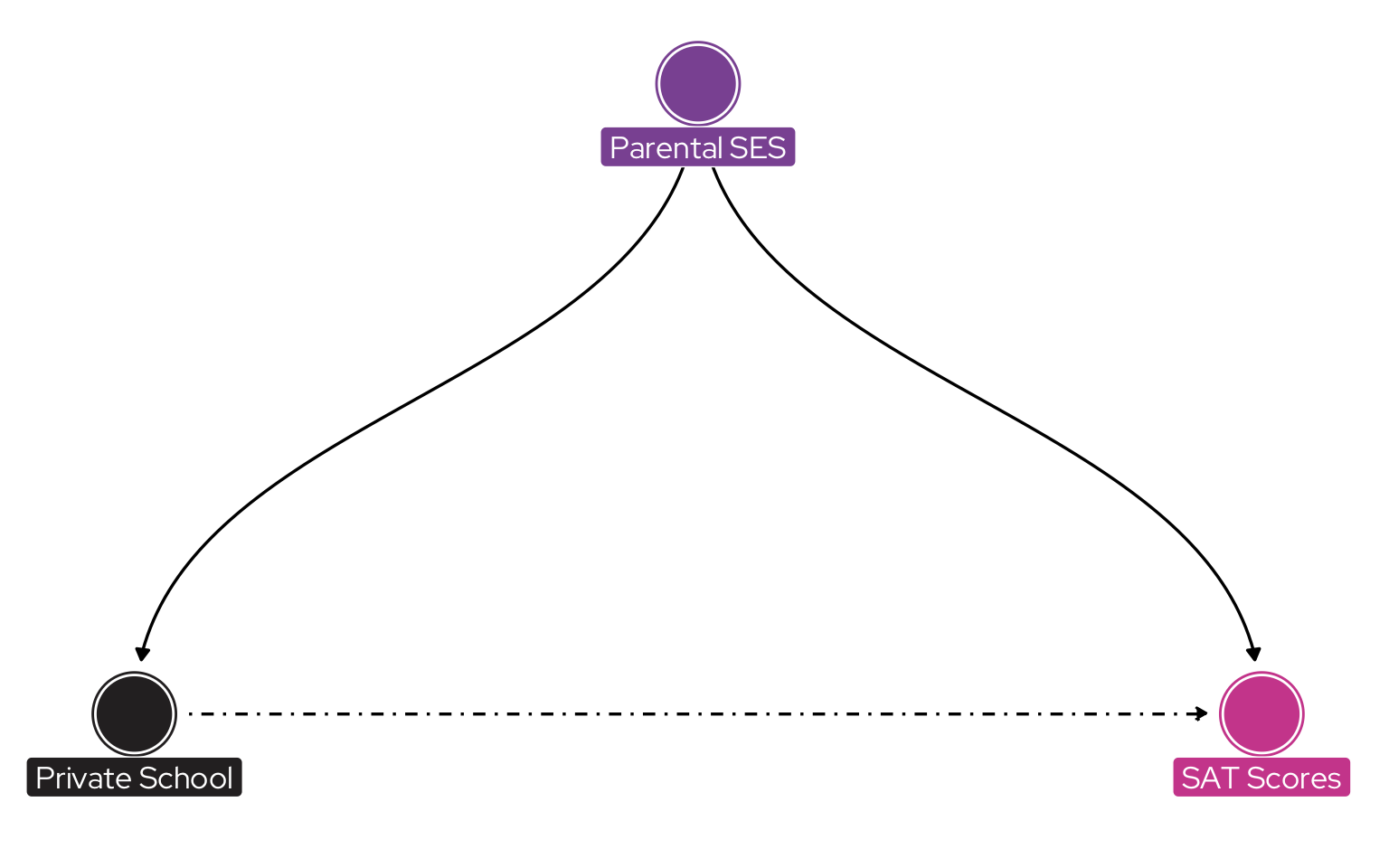

Why might private school attendance and SAT scores be correlated?

Parental socioeconomic status is the confounder in this instance.

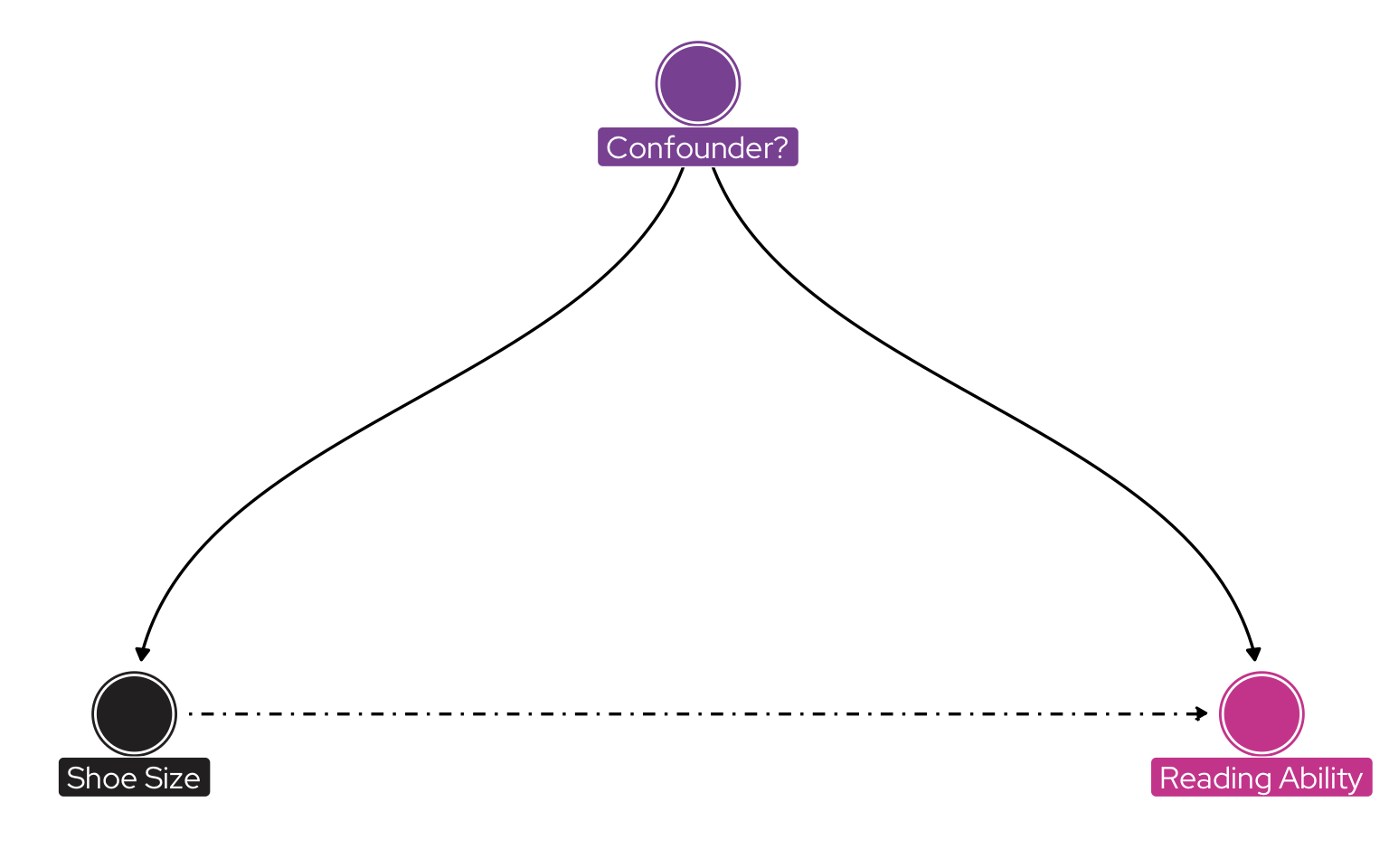

Why might shoe size and reading ability be correlated among children?

Age is the confounder in this instance.